Floating World

Watching viewers stand in front of my Rose Parade paintings, eclipsing the patterns with the silhouette of their bodies, gave me the idea of bringing figures back into the work and exploring the relationship between figures and landscapes.

I saw an exhibition at The Met in 2019, Tale of the Genji, of work inspired by one of Japan's most celebrated works of literature from the 11th century. I was struck by the power of the white of the paper used as positive rather than negative space, the relationship between tiny figures and sprawling landscapes, the use of gradients, and the creation of depth through overlapping, contrasting, patterns rather than light and shade.

“Floating World” comes from the Japanese term Ukiyo. Ukiyo has a complex history, the more explored the more there is to unpack. The original term was used by the Buddhist monks to mean Sorrowful World, a world of pain and attachment from which they sought release. A homonymn was co-opted in the 1600s to the 1800s to mean Floating World, an ironic reversal employed to advertise the novel pleasures of the geisha, kabuki actors, and the burgeoning red light district of Edo, precursor to modern day Tokyo.

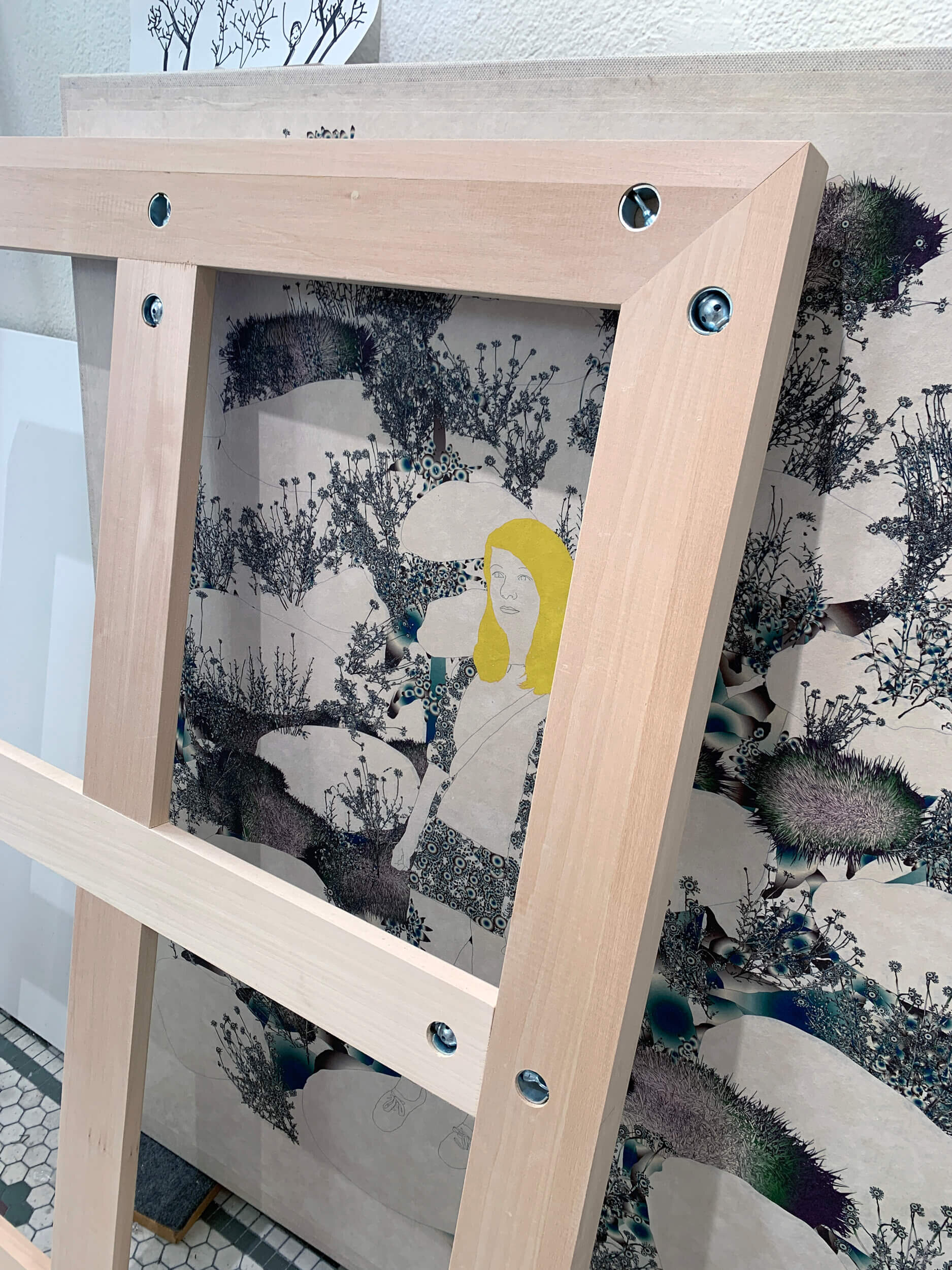

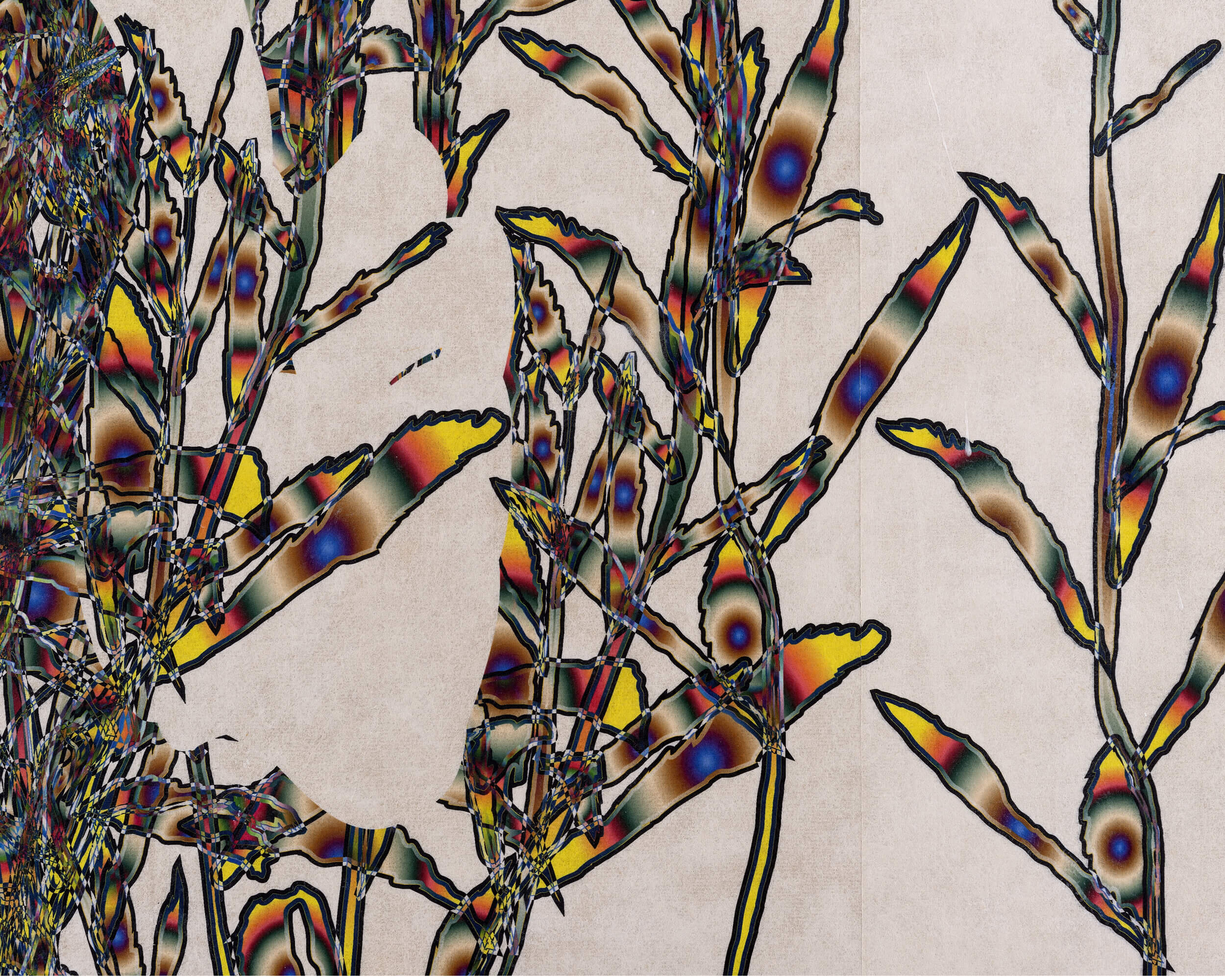

My Floating World is made by digitally, collaging together the individual plant drawings that I have drawn over the last 15 years, and adding new silhouettes of figures into larger, artificial landscapes. They are colored with gradients inspired by traditional ukiyo-e prints, printed onto mulberry paper, and mounted to linen.

The work explores the impermanence of our presence, and our struggle to find a place in a conjured, artificial, and ever more human made world.

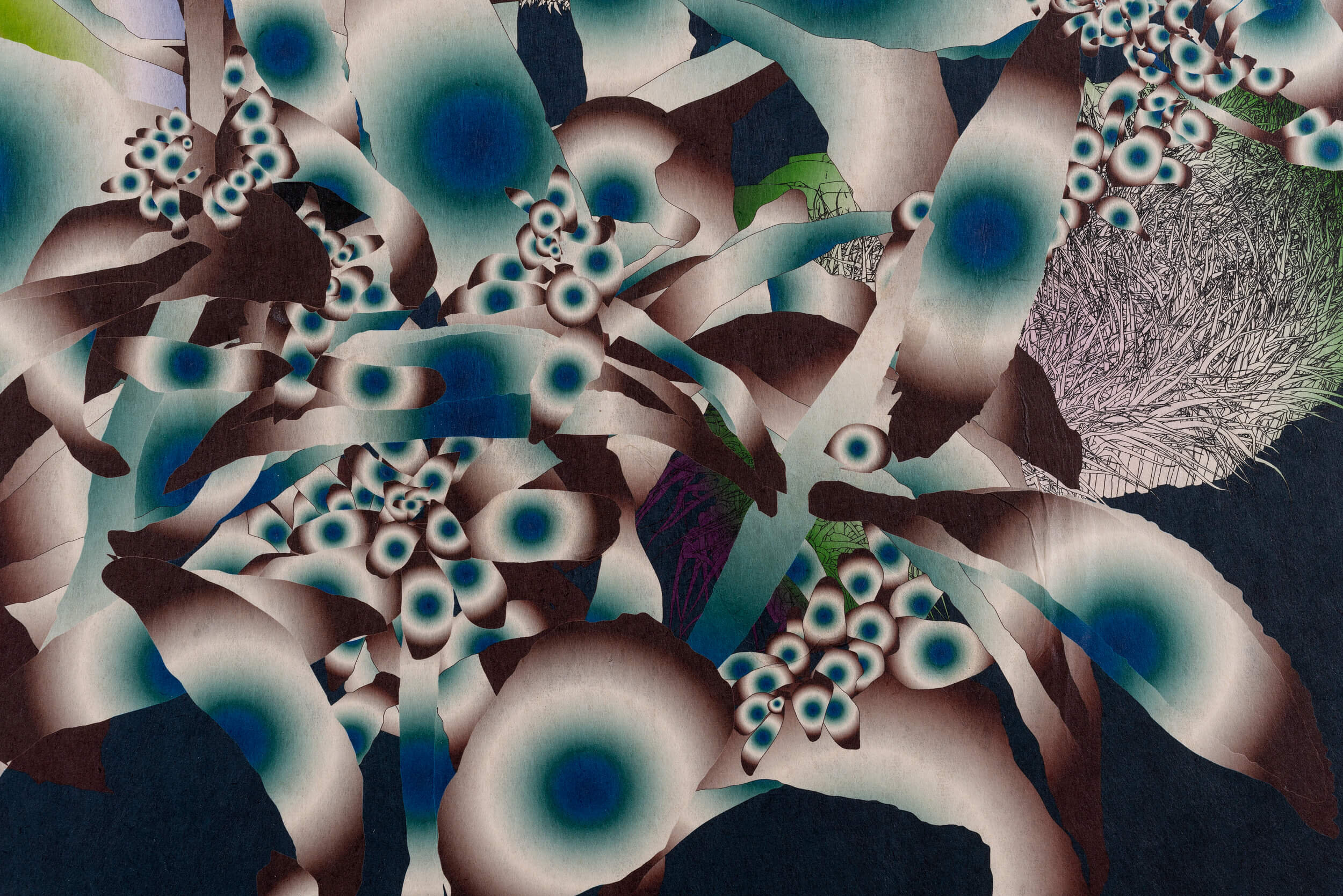

Floating World (The Sleeper)

2021

Pigment print, mulberry paper on linen

86” x 71.5”

Portrait-Icon of Murasaki Shikibu (Murasaki Shikibu zu)

Tosa Mitsuoki (Japanese, 1617–1691)

“What is our role in the natural world? What is our role in our human made world? How does the world change when more and more is made?”

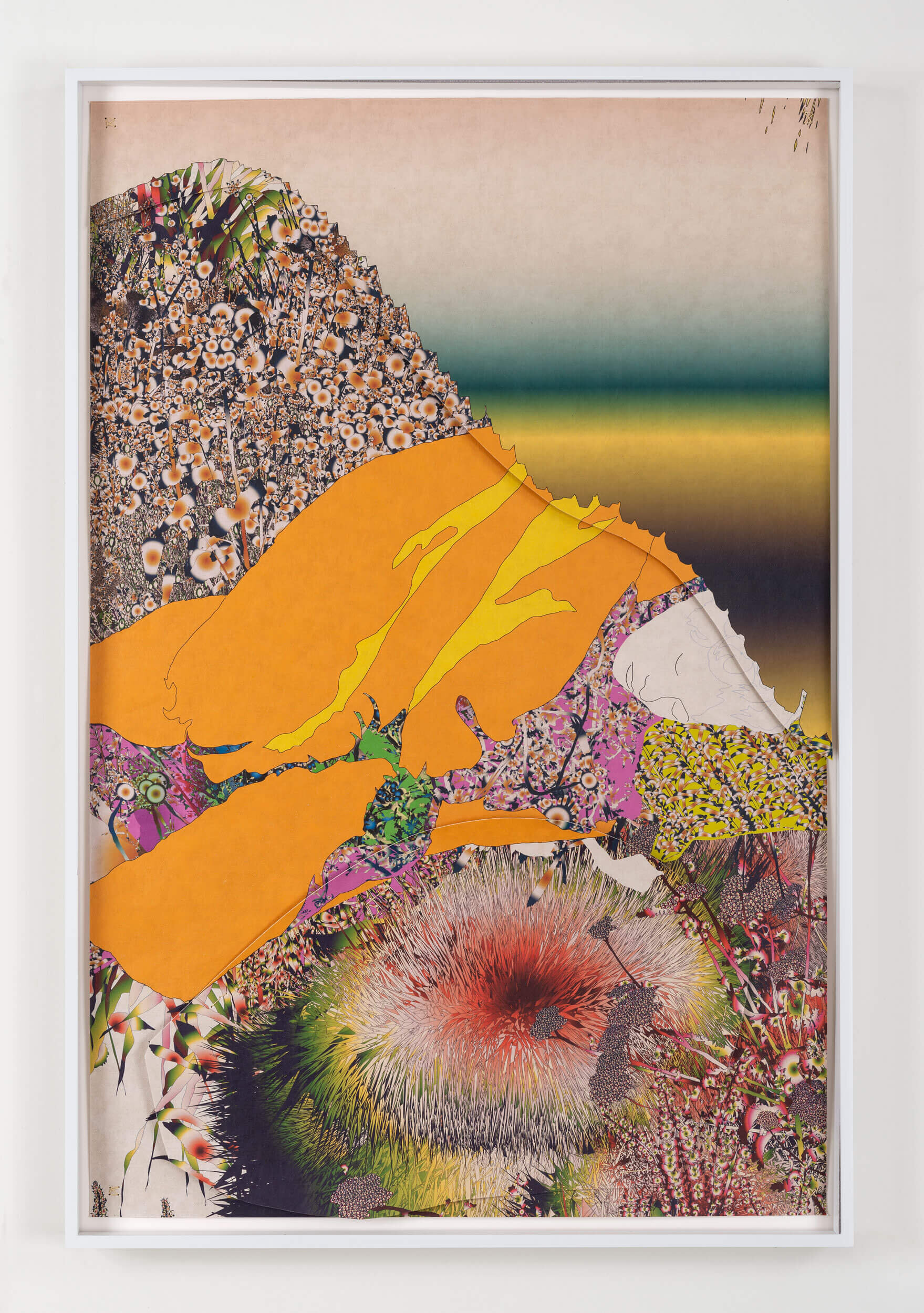

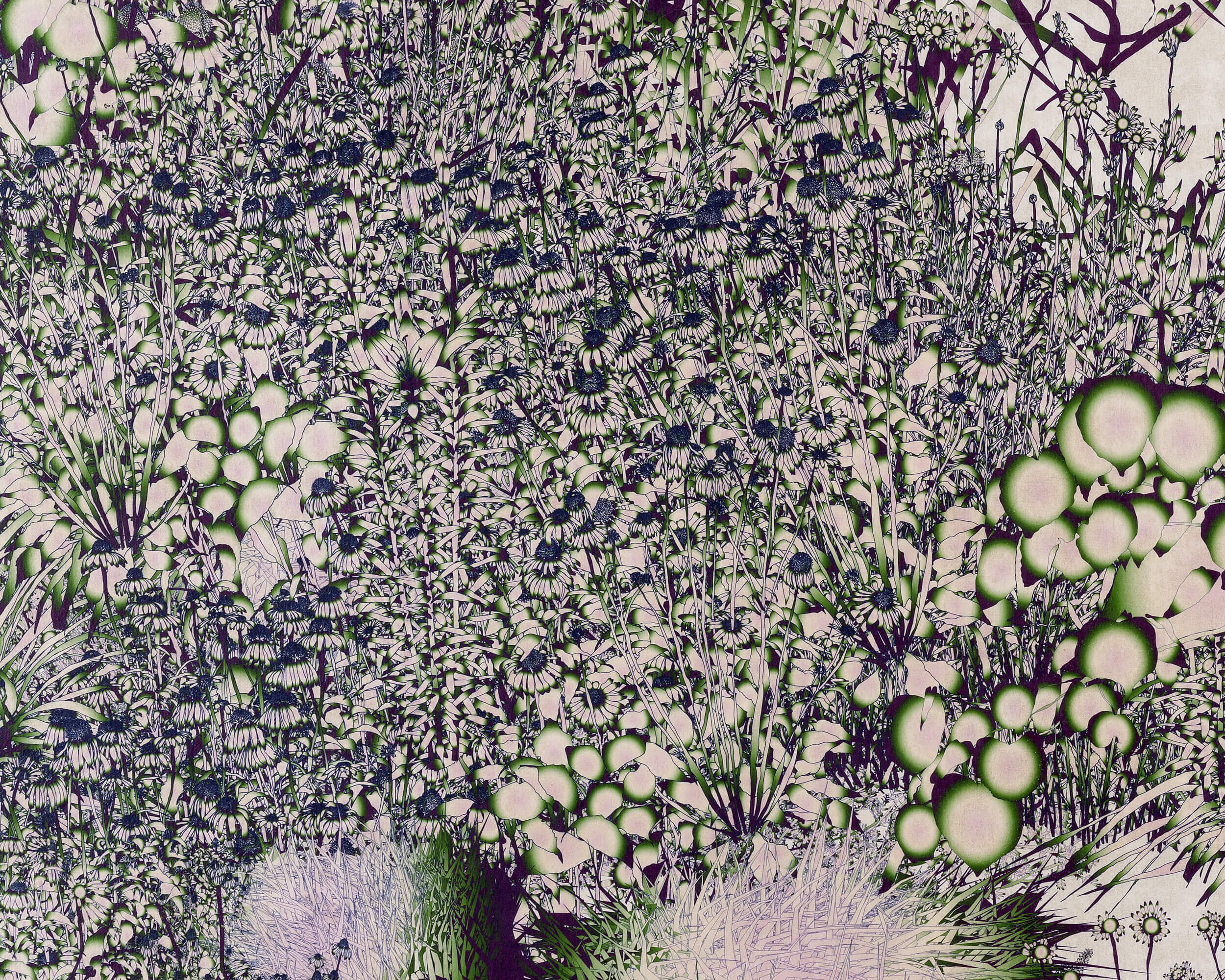

Floating World (The Red Hill)

2021

Pigment print, mulberry paper on linen

86” x 71.5”

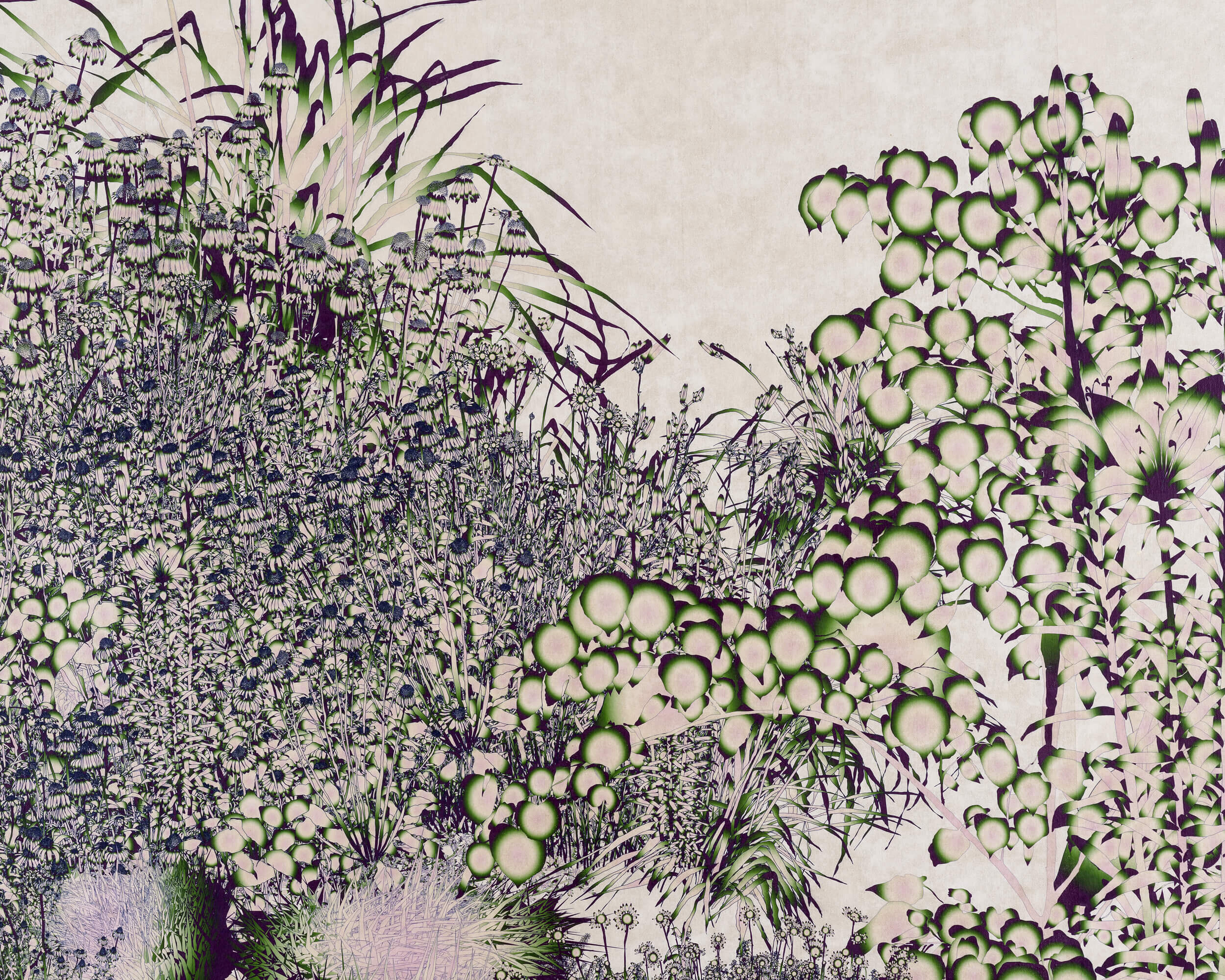

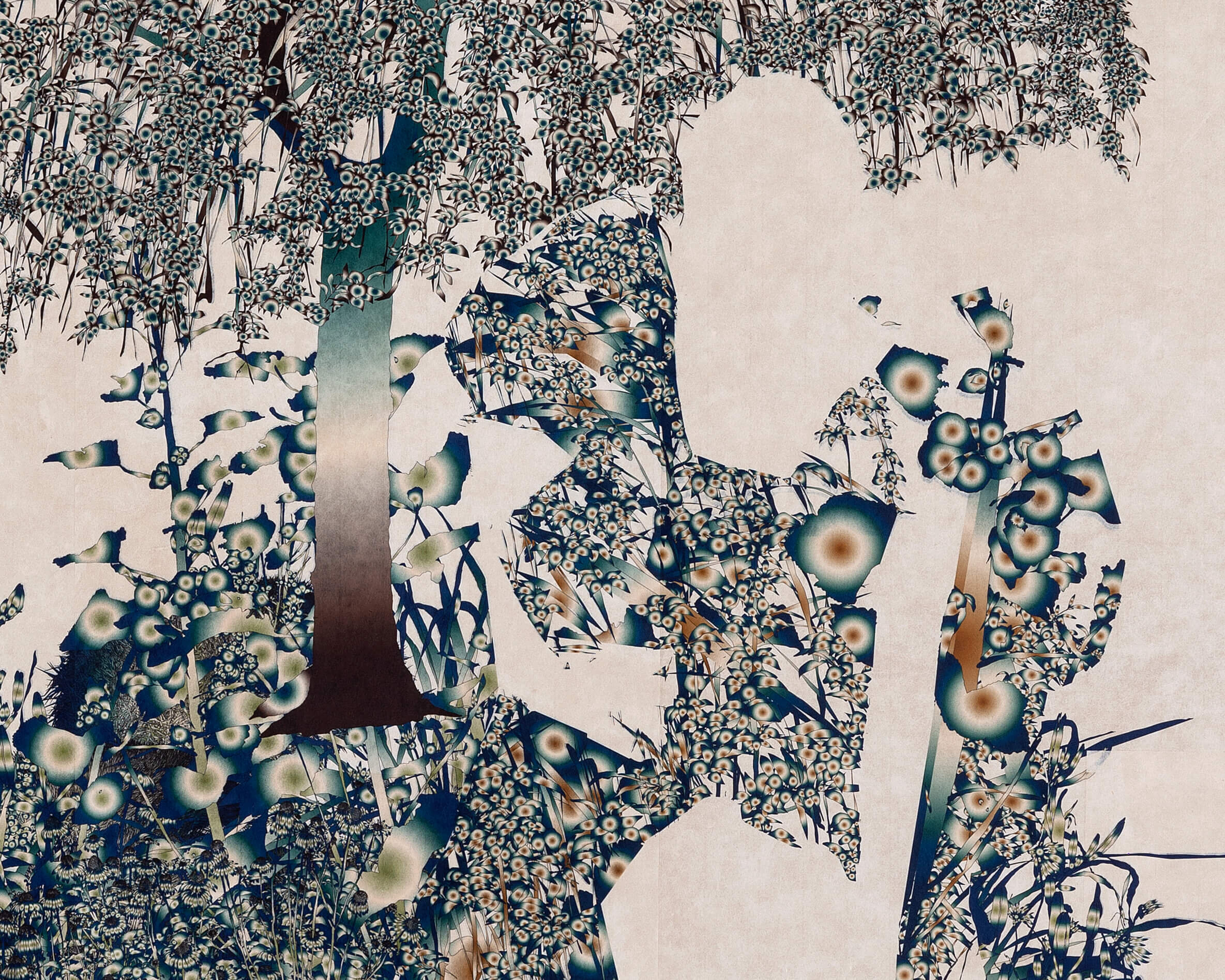

Floating World (Under the Sky)

2021

Pigment print, mulberry paper on linen

45” x 30”

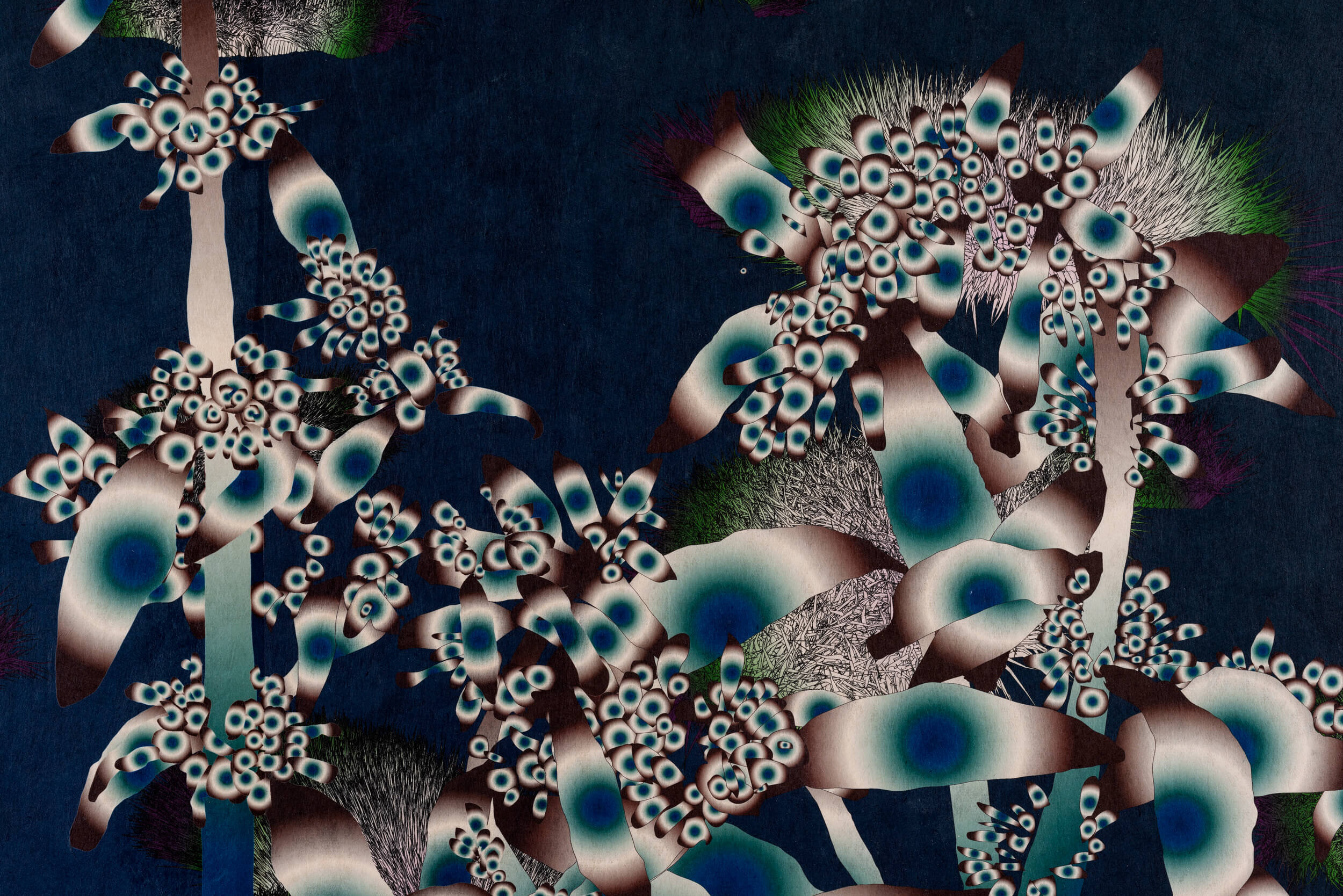

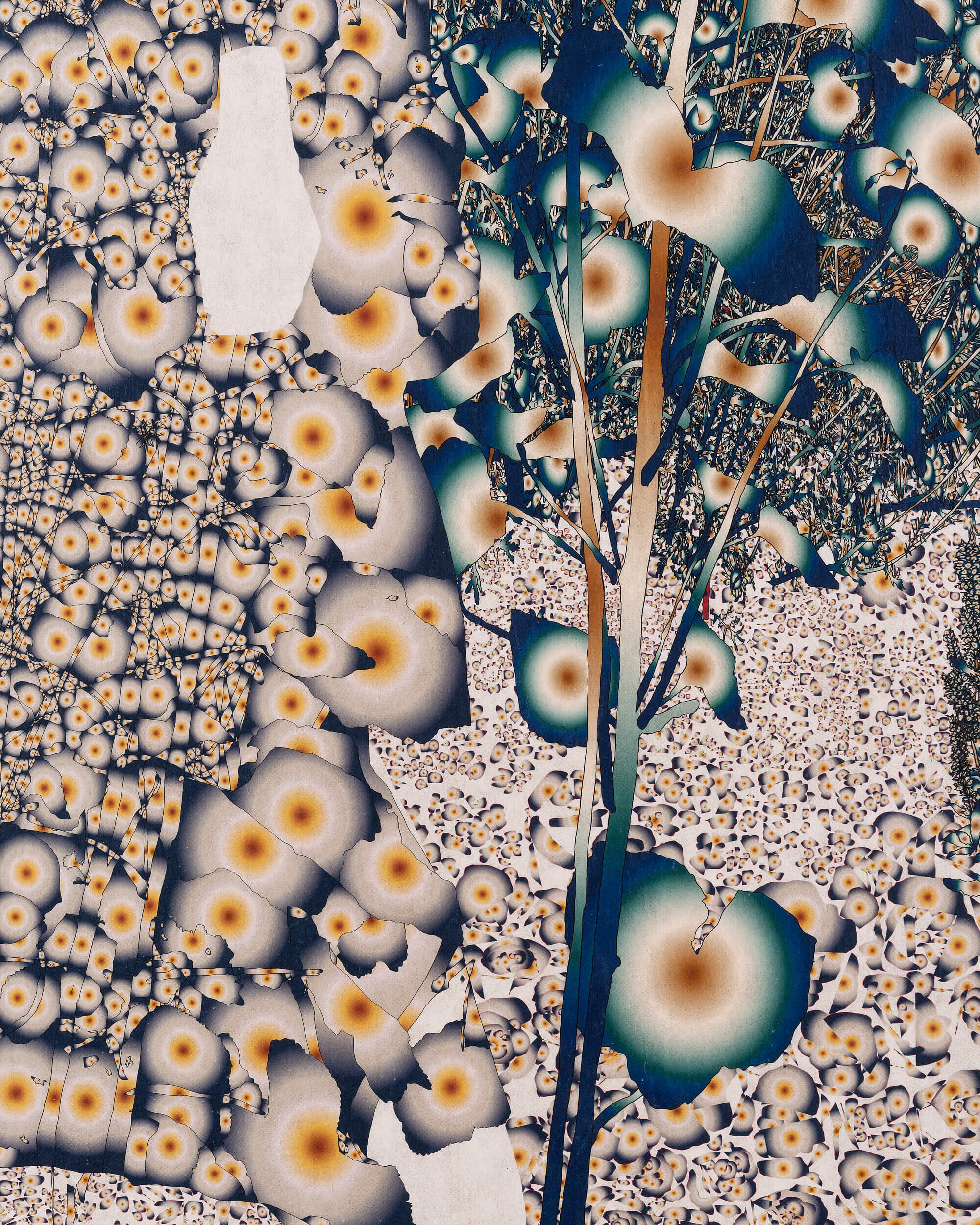

Floating World (Lamb’s Ear)

60” x 57”

Pigment print, mulberry paper on linen

2020

“Ukiyo-e is a composite term of uki(floating), yo (world), and e (pictures) or pictures of the floating world”

Floating World (The Rider) , 78”x 81”, Pigment print, mulberry paper, on linen, 2020

Fantastic Garden: Andrew Millner’s Floating World

By Lisa Melandri, Executive Director of the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis

Andrew Millner’s new work illustrates the complexity, beauty, and controlled chaos of the garden. It offers views into a verdant world, complete with passages of lyrical meadow, sun-dappled glade, and thickly planted prairie. Equally evident is the presence and precision of the artist’s hand. Millner deftly renders the seemingly infinite diversity of shape and pattern that make up the petals of the coneflower or the barrage of lines that describe the slender blades of lily leaves. We are at first engaged with the careful and accurate depiction of plants, but the works in the series Floating World are far more than mere description. Instead, they are infused with memory and trace, absence as well as presence. Some of the works present a ghostly outline or the hint of figures inhabiting the landscape, sometimes foregrounded but often enveloped by the plants, trees, and flowers that are so painstakingly drawn.

A garden implies cultivation, the organization of the natural environment by humans. Even when appearing wild, a garden involves control. The garden also connotes human presence—it is meant to be visited or occupied by people. It is a site for recreational activity and pleasure; and though we may be surrounded by nature, we do not feel small or overwhelmed, instead we feel safe and at ease. The phrase “in the garden” has been used to describe everything from the origin story in the gospels to poetic and metaphorical musings on our place in the world. From the Bob Dylan song to the long-running column in the New York Times, being “in the garden” is synonymous with being in harmony with our environment. Millner has carefully cultivated and composed a lush and multifaceted garden for us to contemplate and enter—both psychologically and emotionally—in myriad different ways.

Floating World comprises a series of large-scale pigment prints on mulberry paper, mounted on linen. Taken together, this body of work describes an entire ecosystem or even a utopian and ethereal parallel universe. Millner’s compositions do not fill the entirety of the picture plane—dense passages fade to the unmarked margins of the paper. Millner uses white space to punctuate and frame his subjects. The title of the series has layered meaning, described in more detail below. However, compositionally, the images indeed float, appearing loosed from their edges, all adding to the timelessness of the imagery.

For the most part, the palette is muted, with dark blue as the predominant color. Figures are described with the white of the paper, while plants are “painted” in greens, pale pinks, rust orange, and the occasional digital rainbow spectrum. In spite of passages of bolder color, the overall impression remains that of an ink on paper drawing—or an etching or even a woodblock print.

Floating

The title of the series recalls the eponymous description of urban society in Edo Japan (1615-1868). “Floating World,” or ukiyo, was the term used for the pleasure-seeking culture in urban centers, including brothels, teahouses, theaters, and an array of entertainments for the growing middle class. This cultural moment was illustrated in well-known Japanese woodblock prints known as ukiyo-e, or “pictures of the Floating World,” where geisha, sumo wrestlers, samurai, and kabuki actors featured heavily. These pictures offered documentation, but perhaps, more importantly, access and entry to the sensibility of the times, inviting and implicating the viewer in the indulgences of the moment. Interestingly, ukiyo, connoting a world of play and pleasure, has a homophone (also sounding like ukiyo) meaning quite the opposite—sorrowful world. Millner has thoughtfully chosen the title of his series as it evokes the idea of a buoyant alternate universe, evanescent and enchanting, while also being tied to sadness, the banal, and the limitations of the earth-bound.

“Floating World” is now used to describe a state of being unhindered by the troubles of life. But in the case of Millner’s series, the double meaning invokes the complex duality of human and nature. These works bring forth the pure sensory pleasures of the landscape, while simultaneously calling out the garden as a place where abundance is fleeting. The garden is the ultimate metaphor for lifecycle—birth, generation, and death.

Plants

While sometimes appearing abstract due to the accumulation of lines, Millner offers a horticulturalist’s dream. Every stigma of the yarrow, each petal of the daisy, the fat leaf of the lamb’s ear is outlined. All are at once recognizable. The artist has been “collecting” images of plants in his surroundings over many years. He has carefully drawn each from photographs and transcribed their shapes into vector files, important to note as these files can be reproduced at any scale without losing definition or becoming pixelated. Millner draws each plant on the Wacom tablet using a stylus and has amassed a botanical library with many species, from chamomile flower to dogwood tree. Even though he is using contemporary tools, Millner is committed to an old-fashioned drawing practice. And one that is close to obsessive in repetition, privileging labor. In many ways, the artist can be compared to a traditional botanist, making sure to accurately depict each species—in a variety of growing patterns and from an array of perspectives. In this way, he can construct a calibrated image of the garden, layering and compositing various elements to create the final landscape in each work.

In Floating World (The Party) a weeping cherry defines the edge of a glade dense with yarrow, coneflowers, and the elongated blooms of salvia. The largest blooms, hollyhocks, and the broadest leaves appear to be illuminated from their centers, radiating a color spectrum. Millner employs the gradient tool in Illustrator to portray light and color bursts that comprise some of the most striking visual passages in the series. This effect fills the outlines, turning line drawings into paintings, monochromes into polychromes.

Floating World (Perennial) and Floating World (Lamb’s Ear) delight in hyper-charged, almost psychedelic horticultural description. They function as portraits of the natural world. Tufts of grass become characters, lit-up from within, sometimes placed at the periphery, sometimes punctuating the composition, seeming to have an anthropomorphic presence. The ecstatic density of wildflowers in Perennial alludes to the profusion of untamed prairie. Upon close inspection, rocks become faceted jewels, round blooms become floating lanterns. While exacting and true to nature, through Millner’s hand, plants are transformed, transcending the quotidian towards a heightened plane of perception.

Figures

In Floating World (Heliotrope), a woman stands at center, portrayed in negative space. She is a reverse, featureless silhouette, draped in a dress and wearing a hat fashioned of glowing blooms. The woman is a specter, a trace. Similarly, front and center are horse and rider in Floating World (The Rider) and the figure in a resolute, stable stance in Floating World (The Keeper). In both works, each personage is “dressed” in botanicals but devoid of specific features. The titles of each work are descriptive (those explosive flowers are heliotropes), but The Keeper is perhaps most evocative. Cast as part sentinel, part overseer, maybe matriarch, the figure’s stalwart pose and floral robe suggest knowledge and wisdom, conjuring a timeless narrative.

Floating World (The Party), Floating World (The Park), and Floating World (The Sower) offer slightly different modes of figuration. Here the people and birds are enveloped, partially hidden, and obscured by nature. Rather than appearing ahead of or passing through the landscape, these characters are within nature; they reside in the garden. It is difficult to make out how many figures are included, and, in some cases, whose limbs belong to whom. In these works, person and plant are interchangeable.

Floating World comprises an alternate universe—one where things we recognize are transformed into dreamscape. While grounded in a nature that we can identify, the otherworldly quality of the work creates the sense that we have come upon a window into another time and place. Millner’s garden is lush and inviting, but it is also spectral and somewhat mysterious. Millner’s garden is fantastic.

Floating World (The Keeper) , 78”x 90”, Pigment print, mulberry paper, on linen, 2020

To learn more about this work or inquire about availability, get in touch.